Recursion is fundamentally the idea of defining a function in terms of itself. This sounds trippy and unnecessary, so let's look at a canonical example. The 'hello world' of a recursive functions is

function fibbonacci(n) { ... }The fibonnaci sequence is the sequence of numbers

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8 ...

So the n-th digit in the sequence is the sum of the previous two digits in the sequence. In other words

function fibbonacci(n) {

return fibbonacci(n-1) + fibbonacci(n-2);

}Q: This isn't quite complete though, right? - what is the issue with the above function definition?

Stack Overflow is a term you have likely encountered because of stackoverflow.com, the premiere internet destination to have problems asked and answered. But what is a Stack Overflow? What is the Stack?

Every time a function is called, the programming environment that evaluates that function puts it on 'the stack'. The stack is a data structure that grows to accomodate functions called within functions. So, if I execute the code:

function greet(name) {

return `Hello ${name}!`

}

function printGreeting(name) {

const result = greet(name);

console.log(result);

}

printGreeting('Ben');Q: Can anyone trace what the stack looks like while it's executing this code?

The stack grows like so:

// stack starts out empty

stack_pointer -> []// add function execution to stack

stack_pointer -> [printGreeting('Ben')]// stack grows until we hit a return statement

stack_pointer -> [executing body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// executing body of printGreeting w/ name = 'Ben'

stack_pointer -> [let result = greet('Ben')]

[executing body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// executing body of greet w/ name = 'Ben'

stack_pointer -> [executing body of greet]

[let result = greet('Ben')]

[executing body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// replace latest stack frame with returned value

stack_pointer -> ['Hello Ben!']

[let result = greet('Ben')]

[executing body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// replace function call with returned value

stack_pointer -> [result = 'Hello Ben!']

[execute body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// console.log called at this point

stack_pointer -> [console.log('Hello Ben!')]

[execute body of printGreeting]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// function ends, implicitly calling return undefined

stack_pointer -> [undefined]

[printGreeting('Ben')]// DONE!

stack_pointer -> []So what is a Stack Overflow? Well the stack can't grow infinitely. However, if we called our fibonacci function as it was defined above, that's exactly what would happen! We keep adding stack frames, but we never give the condition to start popping them off! What we need is a base case.

function fibbonacci(n) {

if (n <= 1) return 1;

return fibbonacci(n-1) + fibbonacci(n-2);

}Our base cases define the first two digits of the sequence, and the recursive definition handles all other cases. Great!

Optimal substructure can be found more generally though in terms of data structures that are defined in terms of themselves. Algorithms involving Arrays, Linked Lists and Trees can all generally be thought of recursively, though some are a better fit than others.

function searchArr(arr, value) {

for (let i=0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i] === value) {

return value;

}

}

return -1;

}Q: What's a general approach to converting an algorithm from iterative to recursive?

function searchArr(arr, value) {

if (arr.length === 0) return -1;

let head = arr[0],

tail = arr.slice(1);

if (head === value) return value;

return searchArr(tail, value);

}wdad

What did we change?

- We added a base case - when our array is empty

- We broke our problem into sub-problems

- does the current element match value?

- if yes, return that value

- if not, recursively search the rest of the array

- does the current element match value?

- We combine the results of the current with the 'rest' to produce the actual result. In this case it is simply returning the value so not a lot of explicit combining!

Let's do the same thing with a Tree

Try to come up with a recursive solution on your own

class TreeNode {

constructor(value) {

this.val = value;

this.left = this.right = null;

}

}

function searchTree(root, value) {

// base case(s)?

// recursive case?

// do we need to combine the results?

}class TreeNode {

constructor(value) {

this.val = value;

this.left = this.right = null;

}

}

function searchTree(root, value) {

if (root.val === value) return root;

let found_left = searchTree(root.left, value);

let found_right = searchTree(root.right, value);

if (found_left) return found_left;

if (found_right) return found_right;

return null;

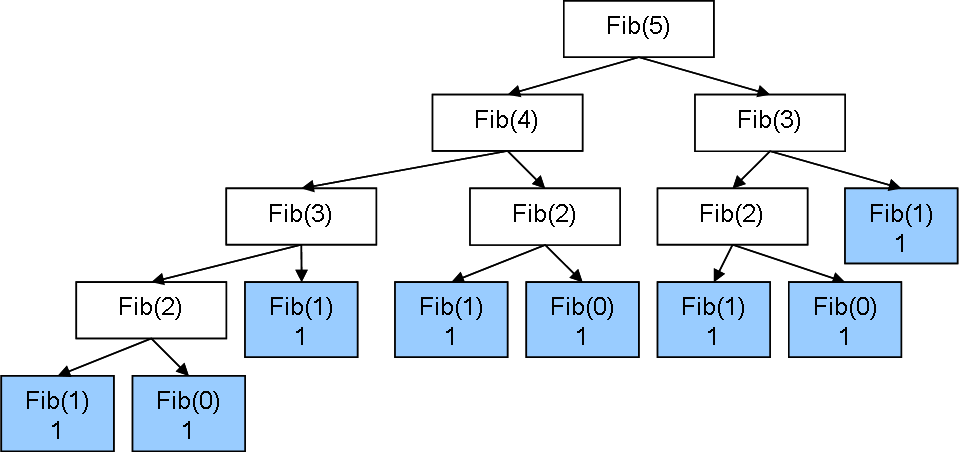

}You may have noticed a problem with our above solution for Fib(n) - a problem that comes up a fair amount when dealing with recursive definitions of functions. That problem can be summed up in this image of the branching call stack of Fib(n)

We are recalculating a number of recursive function calls multiple times! Without going into the details, this obviously will affect time complexity for the worse. So what can we do? Memoization!

Memoization is ultimately a fancy terms for 'saving intermediate values so they don't need to be recalculated'. What does this look like with Fib? Well, we can notice that we calculate the lower values multiple times. What if we reversed the order in which we search for Fib(n), starting with Fib(0)?

function create_memoized_fib() {

let memo = { 0: 1, 1: 1 }

return function memoized(n) {

if (memo[n] !== undefined) return memo[n];

for(let i = 2; i <= n; i++) {

memo[i] = memo[i-1] + memo[i-2];

}

return memo[n];

}

}

let fibbonacci = create_memoized_fib();Q: What does it look lioke when we call Fib(5) with the memoized function? How is this different then the original version?

What does this look like drawn out on a whiteboard?

Dynamic Programming is the set of problems whose runtimes improve when a recursive solution is memoized. Dynamic Programming tells us to compute the solutions to the sub-problems once and store the solutions in so that they can be reused (repeatedly) later. We can see this in the case of Fib(n), but this approach can produce much faster algorithms in unique cases. Identifying where a Dynamic Programming solution can be implemented is difficult, so it's best to work on a problem.

The knapsack problem is a classic example of where a dynamic programming solution can be implemented. Here it is:

Imagine we have a mapping from weight-to-value for a number of, let's say cakes! (This problem is sometimes also called the 'cake-thief problem').

Each index of the two array represents the weights and value of a given cake. We are additionally given a total weight our knapsack can hold - let's say 10(kg). The question - how can we maximize the total value we can fit in the knapsack?

General Approach

- find a recursive definition of the problem

- memoize intermediate results

- find a bottom-up approach to memoization so we don't recalculate anything twice

function getMaxValue(weights, values, limit) {

// ... ???

}

let weights = [1, 2, 4, 2, 5];

let values = [5, 3, 5, 3, 2];

let limit = 10;

getMaxValue(weights, values, limit); // 16