⚠️ ⚠️ This Gist Has Been Moved to This Repo ⚠️ ⚠️

- Features of OOP

- Smart Pointers

- Name Mangling and Externs

- Virtual Functions

- Virtual Base Class

- Friend Functions

- Friend Classes

- Static Functions

- Copy Constructors

- Shallow Copy and Deep Copy

- Operator Overloading

- Namespace

- Templates

- Exceptions

- free vs delete()

- C Storage Classes

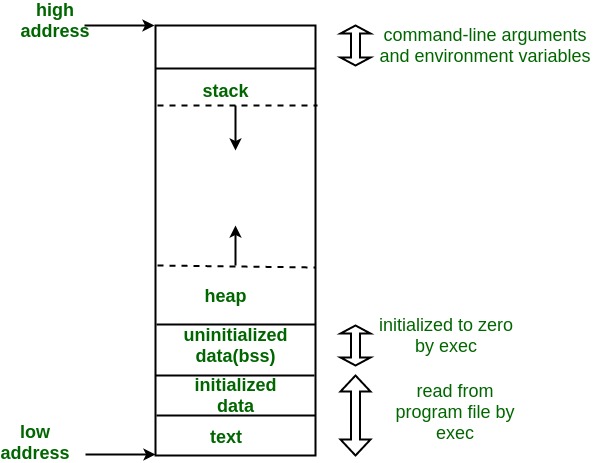

- C Storage Layout

- Credits

-

Abstraction We try to obtain abstract view, model or structure of real life problem, and reduce its unnecessary details. With definition of properties of problems, including the data which are affected and the operations which are identified, the model abstracted from problems can be a standard solution to this type of problems. It is an efficient way since there are nebulous real-life problems that have similar properties.

-

Encapsulation Encapsulation is the process of combining data and functions into a single unit called class. In Encapsulation, the data is not accessed directly; it is accessed through the functions present inside the class. In simpler words, attributes of the class are kept private and public getter and setter methods are provided to manipulate these attributes. Thus, encapsulation makes the concept of data hiding possible. (Data hiding: a language feature to restrict access to members of an object, reducing the negative effect due to dependencies. e.g. "protected", "private" feature in C++).

-

Inheritance The idea of inheritance is simple, a class is based on another class and uses data and implementation of the other class. And the purpose of inheritance is Code Reuse.

-

Polymorphism Polymorphism is the ability to present the same interface for differing underlying forms (data types). With polymorphism, each of these classes will have different underlying data. A point shape needs only two coordinates (assuming it's in a two-dimensional space of course). A circle needs a center and radius. A square or rectangle needs two coordinates for the top left and bottom right corners and (possibly) a rotation. An irregular polygon needs a series of lines.

Pointers with * and -> overloaded. Using smart pointers, we can make pointers to work in way that we don’t need to explicitly call delete. Smart pointer is a wrapper class over a pointer with operator like * and -> overloaded. The objects of smart pointer class look like pointer, but can do many things that a normal pointer can’t like automatic destruction (yes, we don’t have to explicitly use delete), reference counting and more.

The idea is to make a class with a pointer, destructor and overloaded operators like * and ->. Since destructor is automatically called when an object goes out of scope, the dynamically allocated memory would automatically deleted (or reference count can be decremented). Consider the following simple smartPtr class.

#include<iostream>

using namespace std;

class SmartPtr {

int *ptr; // Actual pointer

public:

explicit SmartPtr(int *p = NULL) { ptr = p; }

~SmartPtr() {

delete(ptr);

}

// Overloading dereferencing operator

int &operator *() {

return *ptr;

}

};

int main() {

SmartPtr ptr(new int());

*ptr = 20;

cout << *ptr;

return 0;

}Examples: unique_ptr, shared_ptr

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/extern-c-in-c/

In C++, C function names may not be mangled, as C does not have function overloading feature.

int printf(char *format, ...);

int main() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}Gives -

undefined reference to `printf(char const*, ...)'

ld returned 1 exit statusUse extern C for C codes.

extern "C" {

int printf(char *format, ...);

}

int main() {

printf("Hello, world!");

return 0;

}Constructor can never be virtual function.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Base\n";

}

};

class Derv1: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv1\n";

}

};

class Derv2: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv2\n";

}

};

int main() {

Derv1 derv1;

Derv2 derv2;

Base *ptr;

ptr = &derv1;

ptr -> show();

ptr = &derv2;

ptr -> show();

return 0;

}Output:

Base

Base

This is known as Static/Early Binding. Depends on the type of ptr, not content.

Compile-time/Static polymorphism => Function overloading (this one), Operator overloading

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

virtual void show() {

cout << "Base\n";

}

};

class Derv1: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv1\n";

}

};

class Derv2: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv2\n";

}

};

int main() {

Derv1 derv1;

Derv2 derv2;

Base *ptr;

ptr = &derv1;

ptr -> show();

ptr = &derv2;

ptr -> show();

return 0;

}Output:

Derv1

Derv2

Prepend virtual keyword to the function definition => virtual function.

The rule is that the compiler selects the function based on the contents of ptr, not type. Type is used in non-virtual case.

Here the compiler does not know what class the contents of ptr may contain. It may content address of an object of the Derv1 class or of the Derv2 class. At runtime, this is decided on the basis of content. When it is known what class is pointed to by ptr, the appropriate version is called. This is known as Late Binding.

Another usage for virtual functions is when we cannot or we don’t want to implement a method for parent class.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

virtual void show() = 0; // pure virtual function

};

class Derv1: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv1\n";

}

};

class Derv2: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv2\n";

}

};

int main() {

Derv1 derv1;

Derv2 derv2;

Base *ptr;

ptr = &derv1;

ptr -> show();

ptr = &derv2;

ptr -> show();

return 0;

}Output:

Derv1

Derv2

The class Base is now an abstract class and cannot be instantiated. Any class with a pure virtual function is an abstract class. Once you’ve placed a pure virtual function in the base class, you must override it in all the derived classes from which you want to instantiate objects. If a class doesn’t override the pure virtual function, it becomes an abstract class itself, and you can’t instantiate objects from it(although you might from classes derived from it). For consistency, you may want to make all the virtual functions in the base class pure.

Abstract classes are also called interfaces in C++.

A Good Example of Late Binding:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Department {

public:

void show() {

cout << "You are in CS dept\n";

}

virtual void getData() = 0;

};

class Professor: public Department {

public:

void getData() {

Department::show();

cout << "You are in Professor section\n";

}

};

class Student: public Department {

public:

void getData() {

Department::show();

cout << "You are in Students section\n";

}

};

int main() {

string s;

cin >> s;

Department *dept;

Student student;

if (s == "S") {

// same as: Department *dept = new Student();

// dept = &student;

dept = new Student();

} else {

dept = new Professor();

}

dept -> getData();

return 0;

}#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Base\n";

}

virtual ~Base() {

cout << "Base destroyed\n";

}

};

class Derv: public Base {

public:

void show() {

cout << "Derv\n";

}

~Derv() {

cout << "Derv destroyed\n";

}

};

int main() {

Base *pBase = new Derv();

delete pBase;

}Deletes both Base and Derv. If not virtual, only “Base” will be deleted.

Source: https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/125-the-virtual-table/

To implement virtual functions, C++ uses a special form of late binding known as the virtual table. The virtual table is a lookup table of functions used to resolve function calls in a dynamic/late binding manner. The virtual table sometimes goes by other names, such as “vtable”, “virtual function table”, “virtual method table”, or “dispatch table”.

First, every class that uses virtual functions (or is derived from a class that uses virtual functions) is given its own virtual table. This table is simply a static array that the compiler sets up at compile time. A virtual table contains one entry for each virtual function that can be called by objects of the class. Each entry in this table is simply a function pointer that points to the most-derived function accessible by that class.

Second, the compiler also adds a hidden pointer to the base class, which we will call *__vptr. *__vptr is set (automatically) when a class instance is created so that it points to the virtual table for that class. Unlike the *this pointer, which is actually a function parameter used by the compiler to resolve self-references, *__vptr is a real pointer. Consequently, it makes each class object allocated bigger by the size of one pointer. It also means that *__vptr is inherited by derived classes, which is important.

class Base {

public:

virtual void function1() {};

virtual void function2() {};

};

class D1: public Base {

public:

virtual void function1() {};

};

class D2: public Base {

public:

virtual void function2() {};

};Because there are 3 classes here, the compiler will set up 3 virtual tables: one for Base, one for D1, and one for D2.

The compiler also adds a hidden pointer to the most base class that uses virtual functions. Compiler does this automatically.

class Base {

public:

FunctionPointer *__vptr;

virtual void function1() {};

virtual void function2() {};

};

class D1: public Base {

public:

virtual void function1() {};

};

class D2: public Base {

public:

virtual void function2() {};

};When a class object is created, *__vptr is set to point to the virtual table for that class. For example, when a object of type Base is created, *__vptr is set to point to the virtual table for Base. When objects of type D1 or D2 are constructed, *__vptr is set to point to the virtual table for D1 or D2 respectively.

Now, let’s talk about how these virtual tables are filled out. Because there are only two virtual functions here, each virtual table will have two entries (one for function1(), and one for function2()). Remember that when these virtual tables are filled out, each entry is filled out with the most-derived function an object of that class type can call.

The virtual table for Base objects is simple. An object of type Base can only access the members of Base. Base has no access to D1 or D2 functions. Consequently, the entry for function1 points to Base::function1(), and the entry for function2 points to Base::function2().

The virtual table for D1 is slightly more complex. An object of type D1 can access members of both D1 and Base. However, D1 has overridden function1(), making D1::function1() more derived than Base::function1(). Consequently, the entry for function1 points to D1::function1(). D1 hasn’t overridden function2(), so the entry for function2 will point to Base::function2().

The virtual table for D2 is similar to D1, except the entry for function1 points to Base::function1(), and the entry for function2 points to D2::function2().

The *__vptr in each class points to the virtual table for that class. The entries in the virtual table point to the most-derived version of the function objects of that class are allowed to call.

Parent

/ \

Child1 Child2

\ /

Grandchild

The Diamond problem

If an inherited method from Parent is called from Grandchild, will throw ambiguous error.

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Parent {

protected:

static int basedata;

};

int Parent::basedata = 5;

class Child1 : virtual public Parent { // shares copy of Parent

};

class Child2 : virtual public Parent { // shares copy of Parent

};

class Grandchild : public Child1, public Child2 {

public:

int getdata() {

return basedata; // no longer ambiguous

}

};

int main() {

Grandchild *gc = new Grandchild();

cout << gc -> getdata() << "\n";

return 0;

}The use of the keyword virtual in these two classes causes them to share a single common subobject of their base class Parent. Since there is only one copy of basedata,there is no ambiguity when it is referred to in Grandchild.The need for virtual base classes may indicate a conceptual problem with your use of multiple inheritance, so they should be used with caution.

Accessing private or protected data.

Acts as bridges between two classes.

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Beta;

class Alpha {

private:

int data;

public:

Alpha(): data(3) { };

friend int friendFunction(Alpha, Beta);

};

class Beta {

private:

int data;

public:

Beta(): data(7) { };

friend int friendFunction(Alpha, Beta);

};

int friendFunction(Alpha alpha, Beta beta) {

return alpha.data + beta.data;

}

int main() {

Alpha alpha;

Beta beta;

cout << friendFunction(alpha, beta) << "\n"; // outputs 10

return 0;

}Note the declaration, they can go anywhere (private, protected) not necessarily in public.

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Alpha {

private:

int data;

public:

Alpha(): data(3) { };

friend class Beta;

};

class Beta { // can access all private of Alpha

public:

void func1(Alpha alpha) {

cout << alpha.data << "\n";

}

};

int main() {

Alpha alpha;

Beta beta;

beta.func1(alpha);

return 0;

}#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A {

private:

A() {

cout << "constructor of A\n";

}

friend class B;

};

// class B, friend of class A

class B{

public:

B(){

A a1;

cout << "constructor of B\n";

}

};

int main(){

B b1;

return 0;

}Outputs:

constructor of A

constructor of B

However, if we try to instantiate A, we will get error: _main.cpp:25:7: error: ‘A::A()’ is private within this context.

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Gamma {

private:

static int total;

int id;

public:

Gamma() {

++ total;

id = total;

}

~ Gamma() {

-- total;

cout << "Destroying id number " << id << "\n";

}

static void showTotal() {

cout << "Total is " << total << "\n";

}

void showid() {

cout << "ID is " << id << "\n";

}

};

int Gamma::total = 0;

int main() {

Gamma g1, g2;

Gamma::showTotal(); // without static won't work; i.e., static void showTotal() will work

// but void showTotal() won't

Gamma g3;

Gamma::showTotal();

g1.showid();

g2.showid();

g3.showid();

cout << "End of Program\n";

return 0;

}Outputs:

Total is 2

Total is 3

ID is 1

ID is 2

ID is 3

End of Program

Destroying id number 3

Destroying id number 2

Destroying is number 1

Note the order of destructions. Clearly shows the LIFO stack underneath.

#include<iostream>

using namespace std;

class Point {

private:

int x, y;

public:

Point(int x1, int y1) {

x = x1; y = y1;

}

// Copy constructor

Point(const Point &p2) {

x = p2.x;

y = p2.y;

}

int getX() {

return x;

}

int getY() {

return y;

}

};

int main() {

Point p1(10, 15); // Normal constructor is called here

Point p2 = p1; // Copy constructor is called here

Point p3(p1); // Copy constructor, different syntax

// Let us access values assigned by constructors

cout << "p1.x = " << p1.getX() << ", p1.y = " << p1.getY();

cout << "\np2.x = " << p2.getX() << ", p2.y = " << p2.getY();

cout << "\np3.x = " << p3.getX() << ", p3.y = " << p3.getY();

return 0;

}C++ provides default copy constructors to all classes.

Default copy constructor only does shallow copy, i.e., a member by member copy.

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Counter {

private:

unsigned int count;

public:

Counter(): count(0) {}

unsigned int getCount() {

return count;

}

void operator ++ () {

++count;

}

};

int main() {

Counter c1, c2, c3;

++ c1;

cout << c1.getCount() << "\n"; // 1

++ c2;

cout << c2.getCount() << "\n"; // 1

cout << c3.getCount() << "\n"; // 0

}Note the return value of the operator method. If we try c4 = ++ c1, compiler will complain since the operator is not returning anything. In order to do that:

Counter operator ++ () { //increment count

++count; //increment count

Counter temp; //make a temporary Counter

temp.count = count; //give it same value as this obj

return temp; //return the copy

}Another elegant way to do this is using nameless temporary object.

Counter operator ++ (int) {

return Counter(count++);

}Arithmetic Operators

Distance Distance::operator + (Distance d2) const {

int f = feet + d2.feet;

float i = inches + d2.inches;

if (i >= 12.0) {

i -= 12.0;

f++;

}

return Distance(f, i);

}

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int value = 10;

namespace first {

int value = 40;

namespace second {

int value = 20;

}

}

int main() {

int value = 30;

cout << value << "\n"; // 30

cout << first::value << "\n"; // 40

cout << first::second::value << "\n"; // 20

cout << ::value << "\n"; // 10

return 0;

}One can do namespace aliasing by: namespace alias = first::second::.

Can also use using keyword: using namespace first.

Unnamed Namespace:

# include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int value = 10;

namespace {

int val = 5;

}

// namespace {

// int val = 6;

// } if included, will throw compilation error

int main() {

cout << val << "\n"; // prints 5

return 0;

}The namespace name is uniquely generated by the compiler.

Templates make it possible to handle many different data types by a single function or class.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <class T>

T abs (T n) {

return n < 0 ? -n : n;

}

int main() {

cout << abs(5) << "\n";

cout << abs(-5.2) << "\n";

return 0;

}

More Than One Template Argument

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

template <class atype, class btype>

atype find_ (vector<atype> a, btype n, atype k) {

for (btype i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

if (a[i] == k) {

return i;

}

}

return static_cast<atype>(-1);

// return -1;

}

int main() {

cout << find_({-1.0, 2.1, 3.0}, 3, 2.1) << "\n";

return 0;

}#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

template <class Type>

class Stack {

private:

Type st[100];

int top;

public:

Stack() {

top = -1;

}

void push(Type var) {

st[++top] = var;

}

Type pop() {

return st[top--];

}

};

int main() {

Stack <float> s;

s.push(123.2);

s.push(236.78);

s.push(6553.1);

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

return 0;

}Systematic, object-oriented way to handle errors generated by C++ errors.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

const int MAX = 3;

class Stack {

private:

int st[MAX];

int top;

public:

class Full {

};

class Empty {

};

Stack() {

top = -1;

}

void push(int var) {

if (top >= MAX - 1) {

throw Full();

}

st[++top] = var;

}

int pop() {

if (top < 0) {

throw Empty();

}

return st[top--];

}

};

int main() {

Stack s;

try {

s.push(123);

s.push(236);

s.push(6553);

s.push(23);

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

cout << s.pop() << "\n";

} catch(Stack::Full) {

cout << "Exception: Stack Full!\n";

} catch (Stack::Empty) {

cout << "Exception: Stack Empty!\n";

}

return 0;

}We can also define exception classes.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Dist {

private:

int feet;

float inches;

public:

class InchesEx {

public:

string origin;

float iValue;

InchesEx(string org, float in) {

origin = org;

iValue = in;

}

};

Dist(int ft, float inc) {

if (inc >= 12.0) {

throw InchesEx("2 arg constructor", inc);

}

feet = ft;

inches = inc;

}

void getDist() {

cout << "Enter feet:";

cin >> feet;

cout << "Enter inches";

cin >> inches;

if (inches >= 12.0) {

throw InchesEx("getDist function", inches);

}

}

};

int main() {

try {

Dist d(5, 13);

} catch (Dist::InchesEx ix) {

cout << "Error!\n" << ix.origin << "\nInches: " << ix.iValue <<"\n";

}

return 0;

}Built-in exception classes: bad_alloc is one example. There are many others in STL.

In C++, delete operator should only be used either for the pointers pointing to the memory allocated using new operator or for a NULL pointer, and free() should only be used either for the pointers pointing to the memory allocated using malloc() or for a NULL pointer.

-

auto: default, they can only be accessed within the block/function they have been declared and not outside them (which defines their scope).

-

extern: This storage class tells that the variable is defined elsewhere and not within the same block where it is used.

-

static: They have the property of preserving their value even after they are out of their scope.

-

register: Uses CPU register.

| Storage Specifier | Storage | Initial Value | Scope | Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| auto | Stack | Garbage | Within block | End of block |

| extern | Data Segment | Zero | global multiple files | Till end of program |

| static | Data Segment | Zero | Within block | Till end of program |

| register | CPU Register | Garbage | Within block | End of block |

Heap: dynamic memory allocation

Stack: function calls, local variables

Uninitialized data (bss): BSS = Block Started by Symbol; all uninitialized global and static variable

Initialized data (ds): DS = Data Segment; explicitly initialized global and static variables

Text: binary of the compiled program, read-only; sharable so that only a single copy needs to be in memory for frequently executed programs such as text editors etc

Portions of this note is taken from geeksforgeeks, Leetcode, learncpp website and, Cracking the Coding Interview and Object-Oriented Programming in C++, Fourth Edition book.

very nicely documented :-)