Here is an essay version of my class notes from Class 10 of CS183: Startup. Errors and omissions are mine.

Marc Andreessen, co-founder and general partner of the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, joined this class as a guest speaker. Credit for good stuff goes to him and Peter. I have tried to be accurate. But note that this is not a transcript of the conversation.

Class 10 Notes Essay—After Web 2.0

I. Hello World

It all started about 40 years ago with ARPANET. Things were asynchronous and fairly low bandwidth. Going “online” could be said to have begun in 1979 with the CompuServe model. In the early ‘80s AOL joined in with its take on the walled garden model, offering games, chat rooms, etc. Having laid the foundations for the modern web, the two companies would merge in ’97.

The Mosaic browser launched in 1993. Netscape announced its browser on October 13th, 1994 and filed to go public in less than a year later. And so began the World Wide Web, which would define the ‘90s in all kinds of ways.

“Web 1.0” and “2.0” are terms of art that can be sort of hard to pin down. But to speak of the shift from 1.0 to 2.0 is basically to speak of what’s changed from decade to decade. When things got going content was mostly static. Now the emphasis is on user generated content, social networking, and collaboration of one sort or another.

Relative usage patterns have shifted quite a bit too. In the early ‘90s, people used FTP. In the late ‘90s they were mostly web browsing or connecting to p2p networks. By 2010, over half of all Internet usage was video transmission. These rapid transitions invite the question of what’s next for the Internet. Will the next era be the massive shift to mobile, as many people think? It’s a plausible view, since many things seem possible there. But also worth putting in context is that _relative _shifts don’t tell the full story. Total Internet usage has grown dramatically as well. There are perhaps 20x more users today than there were in the late ‘90s. The ubiquity of the net creates a sense in which things today are very, very different.

II. The Wild West

The Internet has felt a lot like the Wild West for last 20 years or so. It’s been a frontier of sorts—a vast, open space where people can do almost anything. For the most part, there haven’t been too many rules or restrictions. People argue over whether that’s good or bad. But it raises interesting questions. What enables this frontier to exist as it does? And is the specter of regulation going to materialize? Is everything about to change?

Over the last 40 years, the world of stuff has been heavily regulated. The world of bits has been regulated much less. It is thus hardly surprising that the world of bits—that is, computers and finance—has been the best place to be during the last 40 years. These sectors have seen tremendous innovation. Indeed, finance was arguably _too _innovative. Regulators have taken note, and there’s probably less to do there now. But what about computers? Will the future bring more innovation or less?

Some big-picture Internet developments are on everyone’s radar. Witness the recent and very high profile debates over things like PIPA and SOPA. But other transformations may be just as threatening and less obvious. The patent system, for instance, is increasingly something to worry about. Software patents impose lots of constraints on small companies. Absent regulation, no one can shut you down just because you’re small. But that’s exactly what patents do. Big companies with economies of scale can either afford such regulations or figure out how to skirt them.

III. When Will The Future Arrive?

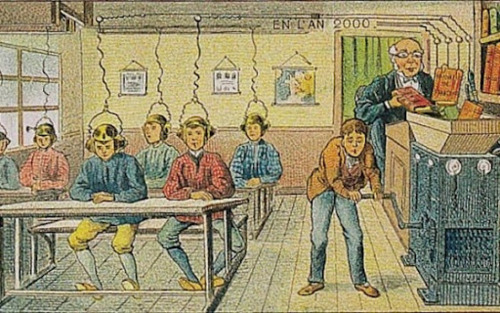

No one knows for sure when the future will arrive. But that’s no reason not to think about the question. It’s easy to point to past predictions where people envisioned a very different future from the one they got. Knowing how and why things didn’t quite unfold as people thought is important. You have to know how people in your shoes have gotten it wrong if you hope to get it right. Instead, we tend to abdicate thinking about the future entirely.

Villemard's 1910 prediction of what schools would be like in 2000. Lessons would be digitally uploaded into children’s brains. But there is still a teacher. There are still desks. And the machine is powered by a hand crank.

Just a few decades ago, people were predicting chemical dinners and heating houses with radium. And being wrong about the future is nothing new. In 1895, Lord Kelvin declared that “heavier than air flying machines are impossible.” U.S. Patent Commissioner Charles H. Duell was confident in 1899 that “everything that can be invented has been invented.” All of that, of course, was spectacularly wrong.

Sometimes bad predictions were just too optimistic. In the ‘60s, people were thinking that everything would soon be nuclear powered. We would have flying cities. Why things haven’t things worked out like that is interesting question to think about. But even more interesting are cases where people _are _right about the future and just wrong on timing. Lots of times people get the call right, but the future takes longer to arrive than they thought.

There is a sense in which AI just doesn’t quite work yet.

Consider mobile technology. People have been betting on mobile for years. Most of them were far too early. Everyone who tried mobile back in ’99 failed. No one thought that the best mobile investment would be to buy a bunch of Apple stock.

There are many more examples. The first rockets were developed in China in the 13th century. But that was not the right time to try to go to the moon. Going to the moon was still a good idea—it just took another couple hundred years for the timing to be right. Apple released its Newton mobile device in 1993, but it took another 15 years before it got the timing right for the iPhone. First we had Napster. It was too early and probably too disruptive. And now we have Spotify. If we learn the right lessons, the future of the past can come back and become true.

IV. Is Software Eating the World?

Marc Andreessen’s most famous thesis is that software is eating the world. Certainly there are a number of sectors that have already been eaten. Telephone directories, journalism, and accounting brokerages are a few examples. Arguably music has been eaten too, now that distribution has largely gone online. Industry players don’t always see it coming or admit it when it arrives. The New York Times declared in 2002 that the Internet was over and, that distraction aside, we could all go back to enjoying newspapers. The record industry cheered when it took down Napster. Those celebrations were premature.

If it’s true that software is eating the world, the obvious question is what else is getting or will soon get eaten? There are a few compelling candidates. Healthcare has a lot going on. There have been dramatic improvements in EMR technology, healthcare analytics, and overall transparency. But there are lots of regulatory issues and bureaucracy to cut through. Education is another sector that software might consume. People are trying all sorts of ways to computerize and automate learning processes. Then there’s the labor sector, where startups like Uber and Taskrabbit are circumventing the traditional, regulated models. Another promising sector is law. Computers may well end up replacing a lot of legal services currently provided by humans. There’s a sense in which things remain inefficient because people—very oddly—trust lawyers more than computers.

It’s hard to say when these sectors will get eaten. Suffice it to say that people should not bet against computers in these spheres. It may not be the best idea to go be the kind of doctor or lawyer that technology might render obsolete.

In the more distant future, there’s another set of sectors what seems ripe for displacement by technology. Broadcast media and space/transportation are two examples. Biology could shift from an experimental science to an informational science. There may be quite a bit of room for software to reshape the intelligence and government sectors. All that may be far off, but there certainly seems to be room for improvement.

How should one assess industries and opportunities if software is really eating the world? Consider a 2 x 2 matrix. On the vertical axis you have two choices: compete with computers or work with computers. This is essentially anti-technology and pro-technology. On the horizontal axis, your choices are: compete against China or work with China. This essentially corresponds to anti-globalization and pro-globalization.

On the globalization axis, it’s probably better to collaborate instead of compete. Competing is too hard. People never really make any money. They just beat each other to bloody pulp. You probably shouldn’t compete with China even if you can win the fight. It’s a Pyrrhic victory.

Similarly, it’s probably wise to avoid competing on the technology axis as well. Even if you can do square roots faster than computers—which people could still do a few dozen years ago—you still shouldn’t try to compete. The computers will catch up and overtake you. Human vs. computer chess has gone pretty badly for humans ever since 1997.

Returning to the globalization axis, you’re left with cooperating with China. That’s better than competing with China. But maybe this isn’t the best route to take, either. There is sense in which too many people are myopically focused on working with China. Collaborating with China may be too competitive at this point. Most everyone focuses on globalization instead of technology.

Now the indirect proof is complete: all that’s left is working with computers. Of course, indirect proof is tricky. Everything may seem to point in one direction, but that direction may not be right. If you were to change your perspective or your inputs, things might point in an entirely new direction. But the indirect proof is still a useful tool. If nothing else seems to work, you should take a closer look at what seems better.

V. Conversation with Marc Andreessen

Peter Thiel: Marc, you’ve been involved in the tech industry for two decades. How did you think about future in 1992? In 2002? Now?

Marc Andreessen: My colleagues and I built Mosaic in 1992. It’s hard to overstate how contrarian a bet that was at the time. Believing in the whole idea of the Internet was pretty contrarian back then. At the time, the dominant metaphor was the information superhighway. People saw advantages to more information. At some point we got 500 TV channels instead of 3. But much better than _more _TV was interactive TV came. That was supposed to be the next big thing. Dominant leaders in the media industry were completely bought in to ITV. Bill Gates, Larry Ellison—everybody thought interactive was the future. Big companies would (continue to) rule. Oracle would make the interactive TV software. The information superhighway, by contrast, would be passive. It wouldn’t be all that different from traditional old media. In 1992, Internet was quirky, obscure, and academic, just as it had been since 1968.

To be fair, the future still hadn’t quite arrived by ‘92. Much of the huge skepticism about the Internet seemed justified. You all but needed a CS degree in order to log on. It could be pretty slow. But clinging to skepticism in the face of new developments was less understandable. Larry Ellison said in 1995 that the Internet would go nowhere because it’d be too slow. This was puzzling, since you could theoretically run Internet on the same wire that people already had coming into their houses. Cable modems turned out to work pretty well. Really, the causes of peoples’ anti-Internet bias back then were the same reasons people fear the Internet today; it’s unregulated, decentralized, and anonymous. It’s like the Wild West. But people don’t like the Wild West. It makes people feel uncomfortable. So to say in 1992 that Internet was going to be the thing was very contrarian.

It’s also kind of path dependent. The tech nerds who popularized and evangelized the web weren’t oracles or prophets who had access to the Truth. To be honest, if we had access to the big power structures and could have easily gone to Oracle, many of us would have fallen in. But we were tech nerds who didn’t have that kind of access. So we just made a web browser.

Peter Thiel: What did you actually think would happen with the Internet?

Marc Andreessen: What helped shape our thinking was seeing the whole thing working at the computing research universities. In 1991-92 Illinois had high-speed 45-megabit connections to campus. We had high end workstations and network connectivity. There was streaming video and real-time collaboration. All students had e-mail. It just hadn’t extended outside the universities. When you graduated, the assumption was that you just stopped using e-mail. That could only last so long. It quickly became obvious that all this stuff would not stay confined to just research universities.

And then it worked. Mosaic was released in late ‘92/early ‘93. In ’93 it just took off. There was a classic exponential growth curve. A mailing list that was created for inbound commercial licensing requests got completely flooded with inquiries. At some point you just became stupid if you didn’t see that it’d be big.

Peter Thiel: Did you think in the ‘90s that future would happen sooner than it did?

Marc Andreessen: Yes. The great irony is all the ideas of the ‘90s were basically correct. They were just too early. We all thought the future would happen very quickly. But instead things crashed and burned. The ideas are really just coming true now. Timing is everything. But it’s also the hardest thing to control. It’s hard; entrepreneurs are congenitally wired to be too early. And being too early is a bigger problem for entrepreneurs than not being correct. It’s very hard to sit and just wait for things to arrive. It almost never works. You burn through your capital. You end up with outdated architecture when the timing is right. You destroy your company culture.

Peter Thiel: In the early and mid 2000s, people were very pessimistic about ‘90s ideas. Is that still the case?

Marc Andreessen: There are two types of people: those who experienced the 2000 crash, and those who did not. The people who did see the crash are deeply psychologically scarred. Like burned-my-face-on-the-stove scarred. They are irreparably damaged. These are the people who love to talk about bubbles. Anywhere and everywhere, they have to find a bubble. They’re now in their 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s. They all got burned. As journalists, they covered the carnage. As investors, they suffered tremendously. As employees, they loaded up on worthless stock. So they promised themselves they’d never get burned again. And now, 12 years later, they’re still determined not to.

This kind of scarring just doesn’t go away. It has to be killed off. People who suffered through the crash of 1929 never believed in stocks again. They literally had to die off before a new generation of professional investors got back into stocks and the market started to grow again. Today, we’re halfway through the generational effects of the dot com crash.

That’s the good news for students and young entrepreneurs today. They missed the late ‘90s tech scene, so they are—at least as to the crash—perfectly psychologically healthy. When I brought up Netscape in conversation one time, Mark Zuckerberg asked: “What did Netscape do again?” I was shocked. But he looked at me and said, “Dude, I was in junior high. I wasn’t paying attention.” So that’s good. Entrepreneurs in their mid-to-late 20s are good. But the people who went through the crash are far less lucky. Most are scarred.

Peter Thiel: Your claim is that software is eating the world. Tell us how you see that unfolding over the next decade.

Marc Andreessen: There are three versions of the hypothesis: the weak, strong, and strongest version.

The basic, weak form is that software is eating the tech/computer industry. The value of computers is increasingly software, not hardware. The move to cloud computing is illustrative. There’s been a shift to high volume, low cost models where software controls. It’s very different from the old model.

The strong form is that software is eating many other industries that have not been subject to rapid technological change. Take newspapers, for example. The newspaper industry has been pretty much the same, technologically, for about 500 years! There had been no significant technological disruption since the 15th century. And then boom! The digital transformation happens, and the industry frantically has to try and cope with the change.

The strongest form is that, as a consequence of all this, Silicon Valley type software companies will end up eating everything. The kinds of companies we build in the Valley will rule pretty much every industry. These companies have software at their very core. They know how to develop software. They know the economics of software. They make engineering the priority. And that’s why they’ll win.

All this is reflected in the Andreessen Horowitz investment thesis. We don’t do cleantech or biotech. We do things that are based on software. If software is the heart of the company—if things would collapse if you ripped out your key development team—perfect. The companies that will end up dominating most industries are the ones with the same set of management practices and characteristics that you see at Facebook or Google. It will be a rolling process, of course, and the backlash will be intense. Dinosaurs are not in favor or being replaced by birds.

Peter Thiel: Are there some industries that are too dangerous to disrupt? Disruptive children go to the principal’s office. Disruptive companies like Napster can get crushed. Can you succeed with head-on competition, even if you have the Silicon Valley model in other respects?

Marc Andreessen: Look at what Spotify is doing, which is something very different than what Napster did. Spotify is writing huge checks to labels. The labels appreciate that. And Spotify put itself in position to write those checks from day one. It launched in Sweden first, for example, because it wasn’t a very big market for CDs. It’s a disruptive model but they found a way to soften the blow. When you start a conversation with “By the way, here’s some money,” things tend to go a little better.

It’s still a high-pressure move. They are running the gauntlet. The jury is still out on whether it’s going to work or not going forward. The guys on the content side are certainly pretty nervous about it. This stuff can go wrong in all kinds of ways. Spotify and Netflix surely know that. The danger in just paying off the content people is that the content people may just take all your money and _then _put you out of business. If you play things right, you win. Play them wrong, and the incumbents end up owning everything.

Peter Thiel: Some context: Netflix ran into trouble a year ago when content providers raised rates. Spotify has tried to protect itself against this by having rolling contracts that expire at different times so that industry players can’t gang up and collectively demand rate hikes.

Marc Andreessen: And record companies are trying to counter by doing shorter deals, and in some cases taking non-dilutable equity stakes. It is possible that they could end up owning all the money and all the equity. Spotify and Netflix are spectacular companies. But, because of the nature of their business, they have to run the gauntlet. In general, you should try the indirect path where possible. If you have to compete, try to do it indirectly and innovate and you may come out ahead.

Peter Thiel: What areas do you think are particularly promising in the very near term?

Marc Andreessen: Probably retail. We’re seeing and will continue to get e-commerce 2.0, that is, e-commerce that’s not just for nerds. The 1.0 was search driven. You go to Amazon or eBay, search for a thing, and buy it. That works great if you’re shopping for particular stuff. The 2.0 model involves a deeper understanding of consumer behavior. These are companies like Warby Parker and Airbnb. It’s happening vertical by vertical. And it’s likely to keep happening throughout the retail world because retail is really bad to start with. There are very high fixed costs of having stores and inventory. Margins are very small to begin with. If you take away just 5 or 10%, things collapse. Best Buy, for example, has two problems. First, people can get pretty much everything online. Second, even if you do want to shop brick and mortar, software is eating up what you can buy at Best Buy in the first place.

Peter Thiel: An online pet food company is the paradigm example.

Marc Andreessen: And that’s not such a bad idea anymore! Diapers.com was bought by Amazon for $450m. Golfballs.com turns out to be a pretty good business. Even Webvan is coming back! The grocery delivery company failed miserably back in the ‘90s. But now, city by city, it’s back, trying to figure out crowdsourced delivery. The market is so much bigger now. There were about 50 million people online in the ‘90s. Today it’s more like 2.5 billion. People have gotten acclimated to e-commerce. The default assumption is that everything is available online now.

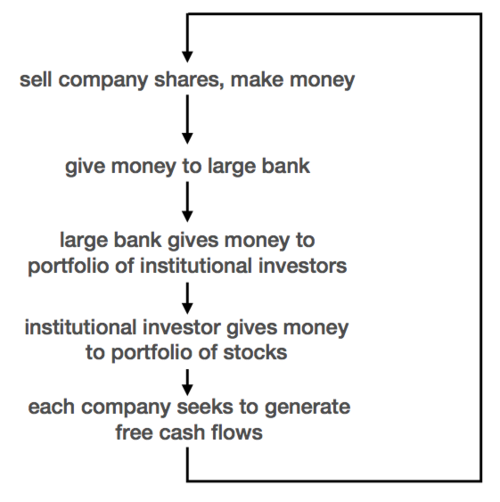

Peter Thiel plays real hedge fund. Andreessen Horowitz plays fake hedge fund. And one if it’s fake hedge fund strategies is short retail, go long e-commerce.

**Peter Thiel: **What new perspectives do you have as VC that are different from your perspectives as entrepreneur? Have you gained any new insights from the other side of the table?

Marc Andreessen: The big, almost philosophical difference goes back to the timing issue. For entrepreneurs, timing is a huge risk. You have to innovate at the right time. You can’t be too early. This is really dangerous because you essentially make a one-time bet. It’s rare are to start the same company five years later if you try it once and were wrong on timing. Jonathan Abrams did Friendster but not Facebook.

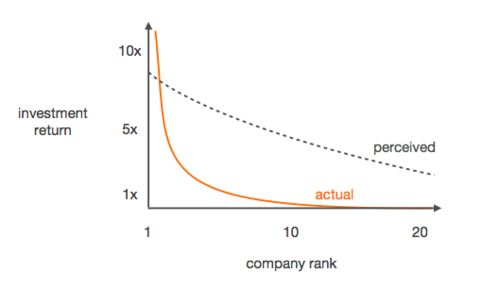

Things are different with venture capital. To stay in business for 20 years or more, you have to take a portfolio approach. Ideas are no longer one-time bets. If we believe in an idea and back the company that fails at it, it’s probably still a good idea. If someone good wants to do the same thing four years later, that’s probably a good investment. Most VCs won’t do this. They’ll be too scarred from the initial failure. But tracking systematically failures is important. Look at Apple’s Newton in the early ‘90s. Mobile was the central obsession of many smart VCs in the Valley. That was two decades too early. But rather than swear off mobile altogether, it made more sense to table it for awhile and wait for it to get figured out later.

Peter Thiel: When people invest and things don’t work out, the right thing to do is course correct. And when people don’t invest and something works, they remain anchored to their original view and tend to be very cynical.

Marc Andreessen: Exactly. The more successful missed investments get, the more expert we become on what’s wrong with them. (Dammit square! J )

But seriously—if you think you can execute on an idea that someone tried 5-10 years ago and failed, good VCs will be open to it. You just have to be able to show that now is the time.

Peter Thiel: What’s the one thing that younger entrepreneurs don’t know that they should?

Marc Andreessen: The number one reason that we pass on entrepreneurs we’d otherwise like to back is focusing on product to the exclusion of everything else. We tend to cultivate and glorify this mentality in the Valley. We’re all enamored with lean startup mode. Engineering and product are key. There is a lot of genius to this, and it has helped create higher quality companies. But the dark side is that it seems to give entrepreneurs excuses not to do the hard stuff of sales and marketing. Many entrepreneurs who build great products simply don’t have a good distribution strategy. Even worse is when they insist that they don’t need one, or call no distribution strategy a “viral marketing strategy.”

Peter Thiel: We’ve discussed before why one should never take it at face value when successful companies say they do no sales or marketing. Because that, itself, is probably a sales pitch.

Marc Andreessen: We hear it all the time: “We’ll be like Salesforce.com—no sales team required, since the product will sell itself.” This is always puzzling. Salesforce.com has a huge, modern sales force. The tagline is “No software,” not “No sales.” AH is a sucker for people who have sales and marketing figured out.

Peter Thiel: It may also be time to rethink complex sales. People have been scarred from the ‘90s experience, where businesses predicated on complex sales failed. It was very hard to get people to do business development deals in the early 2000s. But doing these deals can be very advantageous. Google did a phenomenal BD deal with Yahoo. People don’t typically recognize how great it was for Google. Google doesn’t’ like to talk about it because it only wants to talk about it’s engineering. Yahoo doesn’t want to talk about it because it’s embarrassing.

Question from audience: What are some pitfalls to avoid in thinking about the future?

Peter Thiel: You can go wrong in a few ways. One is that the future is too far away, so you might be right on substance but you’ll be wrong on timing. The other is that the future is here, but everyone else is already doing it.

It’s like surfing. The goal is to catch a big wave. If you think a big wave is coming, you paddle really hard. Sometimes there’s actually no wave, and that sucks.

But you can’t just wait to be sure there’s a wave before you start paddling. You’ll miss it entirely. You have to paddle early, and then let the wave catch you. The question is, how do you figure out when the next big wave is likely to come?

It’s a hard question. At the margins, it’s better err on the side of paddling where there’s no wave than paddling too late and missing a good wave. Trying to start the next great social networking company is current wave thinking. You can paddle hard, but you’ve missed it. Social networking is not the next wave. So the bias should be to err toward the future. Then again, the bigger bias should be to not err at all.

Question from audience: Is it big wave? Or do waves come industry by industry?

Marc Andreessen: Industry by industry. Some industries like finance, law, and health have oligopoly structures that are often intertwined with government. Banks complain about regulation, but are very often protected by it. Citibank’s core competency could be said to be political savvy and navigating through bureaucracy. So there are all sorts of industries with complex regulatory hurdles. It’s fun to see what’s tipping and what’s not. There are huge opportunities in law, for example. You may think those are ripe now, and they may well be. But maybe they are decades out. In VC, you literally never know when some 22 year-old is going to prove everybody wrong.

Question from audience: How do patents relate to the software-eats-the-world phenomenon?

Marc Andreessen: The core problem with patents is that patent examiners don’t get it anymore. They simply don’t and can’t know what is novel versus what isn’t. So we get far too many patents. As a tech company, you have two extreme choices: you could spend your entire life fighting patents, or you could spend all your money licensing usage. Neither of those extremes is good. You need to find the balance that lets you think about patents least. It’s basically a distracting regulatory tax.

Peter Thiel: In any litigation, you have four parties. You have the two parties, and you have the two sets of lawyers. The lawyers are almost always scared of losing. The defense lawyer will talk the client into settling. The question is: do we get somewhere when people are willing to fight to the end to beat back bad patent claims? Or do you have to concede and basically have a patent tax? High litigation costs could be worth it if you only have to fight a few times. The danger is that you fight and win but fail to set any sort of deterring precedent, in which case the suits keep coming and you’re even worse off.

Marc Andreessen: There are some areas in tech—drugs and mechanical equipment, for instance—where parents are fundamental. In these areas there are long established historical norms for who gets to do what. But in software, things change extremely quickly. The big companies used to have huge war chests full of patents and use them to squash little guys. Now they’re fighting each other. The ultimate terminal state of big companies seems to be a state in which they build nothing. Instead, they just add 10,000 patents to their portfolio every year and try to extract money through licensing. It’d be nice if none of this were the case. But it’s not startups’ fault that the patent system is broken. So if you have a startup, you just have to fight through it. Find the best middle ground strategy.

Peter Thiel: In some sense, it may be good to have patent problems. If you have to have problems, these are the kind you want to have. It means that you’ve done something valuable along the way. No one would be coming after you if you didn’t have good technology. So it’s a problem you want to have, even if you don’t.

Question from audience: Has the critical mass of Internet users been reached? Is it harder to be too early now?

Marc Andreessen: For a straight Internet idea, yes. It’s less easy to be too early, which is good. Look at Golfballs.com. Everybody who plays golf is now online. That is a huge change from the ‘90s when far fewer people were dialing up.

Things like mobile are trickier. Some say that smartphones have tipped. We’re currently at about 50% penetration. It may be that things have yet to tip. It seems likely, for instance, that three years from now there will be 5 billion smartphones. The days in which you can buy a non smart phone are probably numbered. And a whole new set of gatekeepers will come with that shift.

Peter Thiel: The big worry with mobile is that any great mobile distribution technique will be disallowed and then copied by Apple and Android. It’s a big market, but it’s far from clear that you can wrest power away from the gatekeepers.

Marc Andreessen: Just recently, Apple blocked any iOS applications from using Dropbox. The rationale was that allowing apps to interact with Dropbox encourages people not to buy stuff through the App Store. That doesn’t seem like a great argument. But it’s like fighting city hall. Even a big important company like Dropbox can get stopped dead in its tracks by Apple.

Question from audience: What have you learned about boards from sitting on boards of successful companies?

Marc Andreessen: Generally, you must try to build a board that can help you. Avoid putting crazy people on your board. It’s like getting married. Most people end up in bad marriages. Board people can be really bad. When things go wrong, the bias is to do something. But that something is often worse than the problem. Bad board members frequently don’t see that.

Peter Thiel: If you want board to do things effectively, it should be small. Three people is the best size. The more people you have, the worse the coordination problem gets. If you want your board to do nothing at all, you should probably make it enormous. Non-profit organizations, for instance, sometimes have boards of 50 people or more. This provides an incredible benefit to whatever quasi-dictatorial person runs the non-profit. A board of that size effectively means no checks on management. So if you want an ineffective board for whatever reason, make it very big.

Marc Andreessen: I’ve never seen a contentious board vote. I’ve seen every other thing go wrong. But never a contentious vote. Problems get dealt with. They either kill the company, or you figure it out in another way.

There is probably too much in the air about optimal legal terms and process. Not enough attention is paid to the people. Startups are like sausage factories. People love eating sausage. But no one wants to watch the sausage get made. Even the seemingly glorious startups only seem that way. They’ve had crisis after crises too. Things go horribly wrong. You fight your way through it. What matters more: what processes you follow? Or who is with you in the bunker? Entrepreneurs don’t think about this enough. They don’t vet their VCs enough.

Question from audience: With businesses like Netflix, it seems like the key thing is customer psychology and behavior, not some technical achievement. But you said you like companies with software at their core. Is there a disconnect?

Marc Andreessen: It’s an “and,” not an “or.” You have to have software at the core, **and **then have great sales and marketing too. That is the winning formula. But properly run software companies have great sales and engineering cultures.

What’s ideal is to have a founder/CEO who is a product person. Sales operators handle the sales force. _The sales force does not build the product! _In poorly run software companies, sales orders product around. The company quickly turns into a consulting company. But if a product person is running the company, he or she can just lay down the law. This is why investors are often leery to invest in companies where you have to hire a new CEO. That CEO is less likely to be the good product person. You can’t just bring in a Pepsi marketing executive to replace Steve Jobs.

Peter Thiel: Are there any exceptions to this? Like Oracle?

Marc Andreessen: No. Larry Ellison is a product guy. Granted, an extremely money-centric product guy. He’s always the CEO. One time he broke his back bodysurfing. He ran the company from the hospital bed. And he’s always had a #2, like Mark Hurd. There’s been a whole series of #2s. But Larry always has a Cheryl.

Salespeople can be very good at optimizing a company over a 2-4 year period. The AH fake hedge fund trade is: when a sales guy replaces a product guy as CEO, go long 2 years, then short.

There are a bunch of exceptions. Meg Whitman gets criticized for late eBay, but early on, she built it up and did a fantastic job. John Chambers clearly did a good job building Cisco, even if things got complicated later on. Jeff Bezos was a hedge fund guy. Good leaders come from all over the place.

Even designers are becoming great CEOs—just look at Airbnb. They’ve got the whole company thinking in terms of design. Design is becoming increasingly important. Apple’s success doesn’t come from their hardware. It comes from OSX and iOS. Design is layered on top of that. A lot of the talk about the beautiful hardware is just the press not getting it. The best designers are the software-intensive ones, who understand it at the deep level. It’s not just about surface aesthetics.

**Question from audience: ** The web browser came out of universities. 10 years later Google came out of Stanford. Do you look at university research departments while searching for great future companies?

Marc Andreessen: Sure. A lot of stuff we’ve invested in was developed in research labs 5-10 years ago. Looking at the Stanford and MIT research labs is a great way of assessing what kinds of technologies might become products in the next couple of years.

Synthetic biology is one example. That might be the next big thing. It’s basically biology—creating new biological constructs with code. This freaks people out. It’s very scary stuff. But it actually seems to work, and it could be huge.

**Question from audience: ** if a certain background isn’t required, what makes for a good CEO?

Marc Andreessen: At AH we think that being CEO is a learnable skill. This is controversial in the VC world. Most VCs seem to think that CEOs come prepackaged in full form, shrink wrapped from the CEO mill. They speak of “world class” CEOs, who usually have uniquely great hair. We shouldn’t be too glib about this; many very successful VCs have the “don’t’ screw around with CEO job” mentality, and maybe they’re right. Their success sort of speaks for itself. But the critique is that that with the “world class” CEO model, you miss out on Microsoft, Google, and Facebook. The CEOs of those companies, of course, turned out to be excellent. But they were also the product people who built the companies. It’s fair to say that the most important companies are founded and run by people who haven’t been CEO before. They learn on the job. This is scary for VCs. It’s riskier. But the payoff can be much greater.

The question is simple: does this person want to learn how to be a good CEO? Some people are psychologically unsuited for the job. Others really want to learn how to do it, and they do well. One thing to learn is that managing people is different than managing managers. Managing managers is scalable. Managing people is not. Once you learn how to manage managers, you’re well on your way to be CEO. You just have to learn enough of the legal stuff to avoid going to jail, enough finance to get money, and enough sales to sell product.

But the Valley is infected by the Dilbert view; everybody thinks management is a bunch of idiots, and that engineers must save the day by doing the right things on the side. That’s not right. Management is extremely important. We are looking for the best outcomes on the power law curve. You have to look at what’s worked well and try to reverse engineer it. Great management and a great product person running the company is characteristic of the very best companies.

Question from audience: What’s more fun: found company or being a VC?

Marc Andreessen: They are pretty different. Generally founders would probably dislike being VCs and vice versa. The typical founder/CEO is a control freak. He would hate VC because VCs can’t give orders. Instead they have to exercise power through influence. But VCs might not enjoy being founders. VCs get the luxury of having opinions without having to execute on them. Executing on them can be really hard and unpleasant. So different people may prefer one or the other. I like them both, but that may not be all that common.

Question from audience: What would you advise entrepreneurial students to do: found a company with a friend from school? Or go work at a 10-person startup?

Marc Andreessen: Starting a company from scratch is hard. Doing it straight out of school is even harder. You could join a small startup to see how young companies work. But there are lots of different ways to learn. It may be better to go to Facebook or Airbnb and see how things work there, because you know what you’ll be learning is what works. That said it’s hard to sit here and advise against starting a company. AH backs founders straight out of school. They can be great founders. But most people benefit from seeing how companies actually work first.

Peter Thiel: The counterargument is that the people behind Google, Microsoft, or Facebook didn’t really have much experience. If you look at very successful companies, it’s very common that the founders had no prior experience at all. The questions to ask when thinking about experience are: what translates? How? If you do join a 10-20 person startup that fails, maybe you learn what not to do. But maybe it would’ve failed for other reasons and you don’t actually learn all the pitfalls. Or maybe you get scarred and never try anything risky again.

What translates from going to work at a big company? The problem with that is that everything kind of works automatically. It’s very difficult to learn about startups if you go work at Microsoft or Google. They are great companies with phenomenal people. But there are shockingly few companies started by those people. One theory is that they are too sheltered. They are just too far removed from startup processes.

Better than thinking about where to go is thinking about what to do. The key questions are: what do you believe in? What makes sense? What’s going to work? If there is indeed a power law distribution in company outcomes, it’s really important to get into the single company you think is the best. The process question of what stage a company is at is less important than the substance of what you’re doing.

Marc Andreessen: I interned at IBM in 1991. It was extremely screwed up. Those of you who follow IBM history will know it as the John Akers era. I was pretty much given the codex of how to screw up a company. You learn _everything _at a dysfunctional company. It was fascinating. Once I got to to see the org chart. There were 400,000 employees. I was 14 levels below the CEO. Which meant that my boss’s boss’s boss’s boss’s boss’s boss’s boss was still 7 levels below the CEO.

The skill that you learn at IBM is how to exist at IBM. It’s completely self-referential. It’s the terminal state. People don’t leave.

Originally posted by Blake Masters. You can find the set of class notes on his site