Alves dos Reis had opened a small checking account with the National City Bank of New York. It took eight days for a check issued in Europe to reach New York by sea. With $40,000 worth of such checks ($600 million today), Reis bought control of Ambaca. When he controlled the company’s reserves he was able to cable the money to New York and make good the checks

-

-

Save neocris/2525adcf37d9c08b7222284387c58f9c to your computer and use it in GitHub Desktop.

On to “the float”! Abagnale explains the scam in detail in his book “The Art of the Steal” (on page 41-43): “Forgers live on the theory that stall creates float and float equals profit.” (The title of this section in the book is “How Buying Time Buys You Money”.)

(As this is a crucial piece of information — remember the word “OCR” in the title of the web site — I’ll quote longer passages from Abagnale’s books for once, but it’s crucial that you understand this fraud mechanism well. I still consider this “fair use” of source material…)

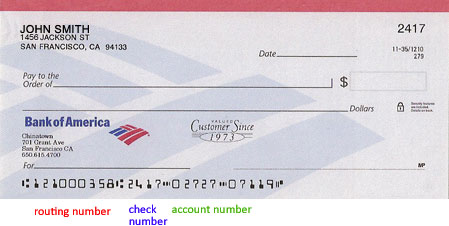

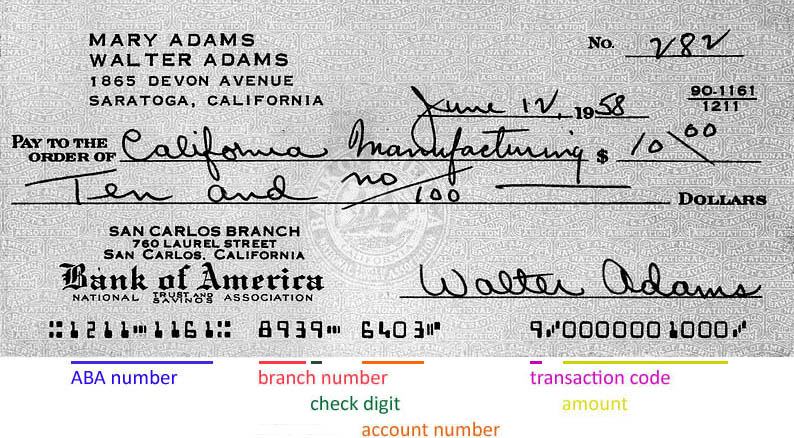

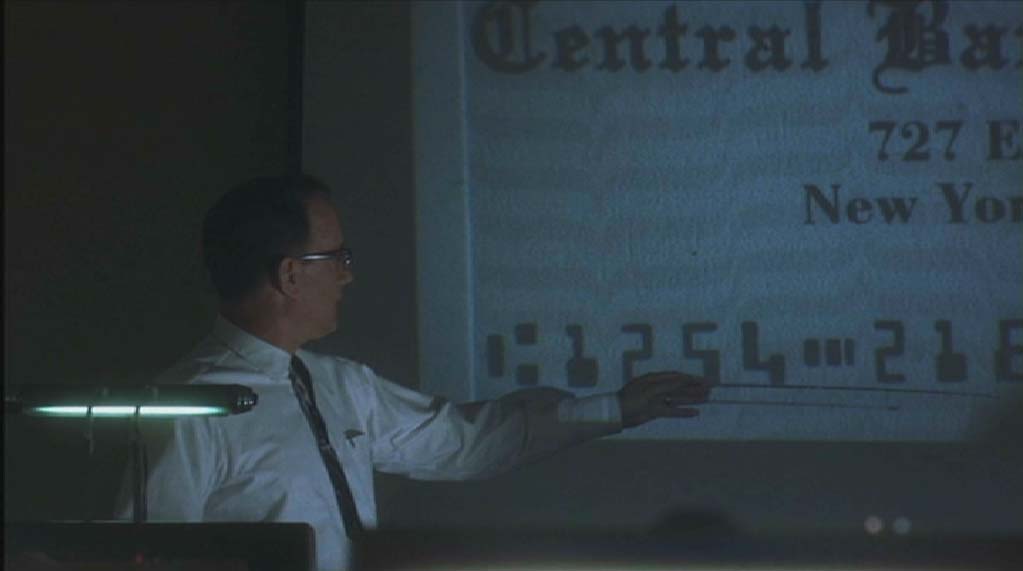

Every good forger alters the numbers along the bottom of the check. Inside a set of brackets is a nine-digit number. That’s the bank’s routing number, and it’s like a ZIP code. When you cash the check, that number allows the check to be sent back to the bank where your account is. The first two digits of that number signify the Federal Reserve Bank in your jurisdiction. For example, New York would be 02. There are twelve Federal Reserve banks scattered around the country; like a dozen eggs, there are a dozen banks. The numbers are assigned from east to west: for instance, 01 is Boston, 03 is Philadelphia, 08 is St. Louis, and 11 is Dallas.

Let’s say that you have a company check from a bank in New York and the company is in New York. You can color-copy fifty of them. That’s quite simple. But if you start cashing them today at supermarkets in the New York area, by tomorrow the bank knows about it and the company will complain that these are forged checks. They call the police, and they send out a bulletin that you’re out there passing bad checks. How many places do you get to in a day? Ten? If you got on the New Jersey Turnpike with all its traffic, you wouldn’t get to the next exit.

But what if I drop the “0” and replace it with a “1”? When I cash the check, the clerk at the courtesy booth at the supermarket will look at the name of the bank and recognize that it’s a New York bank, so it’s a local check and he has no problem cashing it. But when the store deposits the check, by changing that number, just as if I had altered a ZIP code, I force that check to go all the way across the country to Hawaii to clear. When it gets to Hawaii, someone notices that the routing number is incorrect and puts a white strip called a “Lundy strip” across the bottom of the check over the old routing number and sends it back. But by the time that happens, two weeks will have passed. So I have fourteen days instead of one day to wander all over New York cashing bad checks. Forgers live on the theory that stall creates float and float equals profit.

(A “Lundy strip” or “repair strip” is the white adhesive label that a bank affixes to the bottom of a check to correct errors in the codeline.)

“Float” is a financial term. It refers to the duplicate money present in the banking system during the time between a deposit being made in the recipient’s account and the money’s deduction from the sender’s account. Simply put, the float is the time between the negotiation of a check and its clearance at the bank of the check-writer.

Float is very obvious in the use of checks because of the time delay between a check being written and the funds to cover that check getting deducted from the check-writer’s account. Once the recipient of a check — the “payee” — deposits it in his account, his bank credits, increases his account immediately, assuming that the payer’s bank will ultimately transfer the funds to cover the check. Until the payer’s bank actually sends these funds, the payer and payee have the same money in their accounts. Once the payee’s bank notifies the payer’s bank (by presenting the checks), the duplicate funds are deducted from the check-writer’s account and the check is considered to have “cleared” the bank.

The second track of John Williams’ movie score is called “The Float”!

John Williams

“Catch Me If You Can”

Polydor, 2003

ISAN B00007BKUE

Here’s the comprehensive list of the 12 current Federal Reserve Districts…

| **Federal Reserve Districts** | |||

| 01 | Boston | 07 | Chicago |

| 02 | New York | 08 | St. Louis |

| 03 | Philadelphia | 09 | Minneapolis |

| 04 | Cleveland | 10 | Kansas City |

| 05 | Richmond | 11 | Dallas |

| 06 | Atlanta | 12 | San Francisco |

(These districts were established in 1914, as the Federal Reserve System itself! Allowing the Federal Reserve to act as nation-wide check-clearing center shortened the clearing time — until then, often several weeks! — and reduced the excessive exchange rates for checks.)

Government checks have the routing number “000000518”.

There’s the general principle. Let’s take the same, well, “route” again step by step! We’ll use the book “Catch Me If You Can” (page 93) this time. “Below the bank legend, across the bottom left-hand corner of the check, I laid down a series of numbers with magnetic tape. The numbers purportedly represented the Federal Reserve District of which Chase Manhattan was a member, the bank’s FRD identification number and Pan Am’s account number. Such numbers are very important to anyone cashing a check and tenfold as important to a hot-check swindler. A good paperhanger [slang word for check forger] is essentially operating a numbers game and if he doesn’t know the right ones he’s going to end up with an entirely different set stenciled across the front and back of a state-issued shirt.”

We have more info on pages 101-102: “I said earlier that the good check swindler is really operating a numbers game. All checks, whether personal or business, have a series of numbers in the lower left-hand corners, just above the bottoms. Take a personal check that has the numbers 1130 0119 546 085 across the bottom left-hand corner. During my reign as a rip-off champion, not one out of a hundred tellers or private cashiers paid any attention to such numerals, and I’m convinced that only a handful of the people handling checks knew what the series of numbers signified. I’ll decode it.”

The number 11 denotes that the check was printed within the Eleventh Federal Reserve District. There are twelve and only twelve Federal Reserve Districts in the United States. The Eleventh includes Texas, where this check was printed. The 3 after the 11 tells one that the check was printed in Houston specifically, for the Third District Office of the FRD is located in that city. The 0 indicates that immediate credit is available on the check. In the middle series of numbers, the 0 identifies the clearing house (Houston) and the 119 is the bank’s identification number within the district. The 546 085 is the account number assigned the customer by the bank.

How does that knowledge benefit a check counterfeiter? With a bundle in his swag and a running head start, that’s how. Say such a man presents a payroll check to a teller or cashier for payment. It is a finelooking check, issued by a large and reputable Houston firm, payable at Houston bank, or so it states on the face of the chit. The series of numbers in the lower left hand corner, however, starts with the number 2, but the teller or cashier doesn’t notice that, or if (s)he does, (s)he is ignorant of the meaning of the numbers.

A computer isn’t. When the check lands in the clearing-house bank, usually the same night, a computer will kick it out, because, while the face of the check says it’s payable in Houston, the numbers say it’s payable in San Francisco and bank computers read only numbers. The check, therefore, is sorted into a batch of checks going to the Twelfth District, San Francisco in this instance, for collection. In San Francisco another computer will reject the check because the bank identification number doesn’t jibe, and at that point the check lands in the hands of a clearing-house bank clerk. In most instances, the clerk will note only the face of the check, see that it is payable at a Houston bank and hand-mail it back, attributing its arrival in San Francisco to computer error. In any event, five to seven days have passed before the person who cashed the check is aware (s)he has been swindled, and the paperhanger has long since hooked ’em.

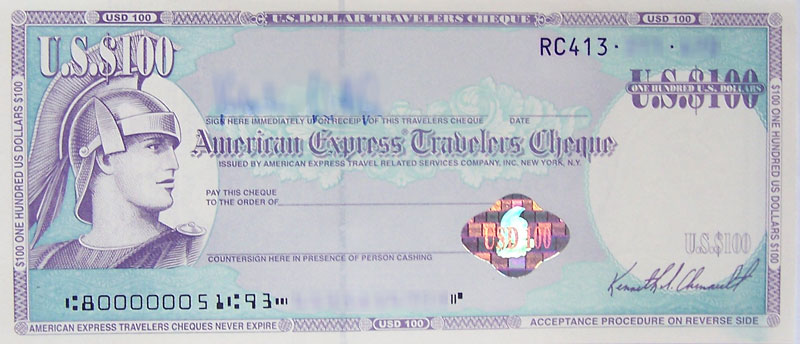

“The Art of the Steal” discusses a scam that’s specific for traveler’s checks (on page 77): “The first thing to know is that all traveler’s checks begin with the routing number 8000. Forgers who forge traveler’s checks go to a great deal of trouble and expense to engrave them. In order to make their money back, they need a lot of time to pass them. To give themselves this time, they will remove the 8000 code and insert the check code of a bank located a far distance from where the checks are being cashed. This will give them just enough time to float those checks so they can cash them.”

Guess what? New legislation has made “the float” easier today than in the old days! This extra info is mentioned in one of Abagnale’s white papers (“Check Fraud and Identify Theft — Volume III” (2004)): “There’s a ‘Federal Reserve Regulation CC’ (from 1992) that reduced the time a bank can hold deposited funds as uncollected items. To give bank customers quicker access to their funds, local checks must be paid within 2 days, non-local checks within 5 days — even if the actual check has not been paid. For instance, if the bank discovers only 10 days later that a check is fake, they’re stuck — the money’s already on the customer’s account. If a bank wants to return a bad check, they have to be much quicker nowadays. And the forgers are well aware that the window available to them has expanded. Manipulating the codeline to the max, they now have extra days to exploit the float!”

Furthermore, any account that has been open for 30 days may no longer be considered a new account — where extended “hold” periods on depoisited funds apply. If you’re a forger, you’d be tempted to open a checking account and wait for a month before you start making use of.

And then there’s a piece of legislation called the “Expedited Funds Availability Act” (“EFAA”). It established another time window that allows a different fraud mechanism called “check kiting”. A check drawn on bank A is deposited in bank B without proper funds to cover the check. Bank B grants the depositor a conditional credit: the depositor can now write checks against these uncollected funds! The depositor goes back to bank A and writes a check drawn on bank B to cover the original check. This game can go on for quite a while… With check kiting, the float is used to delay the notice of non-existing funds.

Check kiting is not illustrated in the movie, it’s just mentioned in passing by Carl Hanratty. When he’s standing a phone boot to inform his colleagues that the Skywayman is actually a kid, he adds this comment: “[...] don’t forget the airports, he’s been kiting checks all over the country.” (scene 12, 1:04:57)

In the book “Catch Me If You Can” (on page 112), Abagnale discusses an extra scam where he made $42,000 dollar by having bank tellers simply slipping money deposit slips of other customers into a machine that stamps — and reads — them.

In the lower left-hand comer of the deposit slip was a rectangular box for the depositor’s account number. I never filled in the box, for I knew it wasn’t required. When a teller put a deposit slip in the small machine in his or her cage, in order to furnish you with a stamped receipt, the machine was programmed to read the account number first. If the number was there, the amount of the deposit was automatically credited to the account holder. But if the number wasn’t there, the account could still be credited using the name and address, so the number wasn’t necessary.

There was a fellow beside me filling out a deposit slip. I noticed he neglected to give his account number. I dawdled in the bank for nearly an hour and watched those who came in to deposit cash, checks or creditcard vouchers. Not one in twenty, if that many, used the space provided for his or her account number.

Surreptitiously I pocketed a sheaf of the deposit slips, returned to my apartment and, using press-on numerals matching the typeface on the bank forms, filled in the blank on each slip with my own account number. The following morning, I returned to the bank and just as stealthily put the sheaf of deposit slips back in a slot atop a stack of others.

You find this scam slightly transformed in the published screenplay (on page 78), but not in the movie! It’s called “the switch”.

(Abagnale later bought a Burroughs 1000 magnetic encoder to add his account number to deposit slips.)

This is only possible because U.S. bank branches are open offices. It’s just desks in a big surface occupied by bank tellers. How are you going to steal forms and put them back in a European bank branch?