In this article, we’ll cover ten proven methods for mastering any skill. You’ll learn how to learn quickly, supercharge your personal growth, and stand out from the crowd without having to spend every living minute bent over text books.

What would you say if I told you there’s a skill that could benefit anyone, any place, any time? Something that would accelerate your progress no matter what career path you chose, indifferent to technological disruptions?

Does that sound too good to be true? Well, here’s the pitch: in a world that’s changing faster than ever, you need to adapt quickly and constantly. That requires the willingness to change, and the ability to learn. Learning quickly — and becoming a life-long learner — should become your new superpower. You won’t be able to stop the world from changing, but with this ability to adapt, you’ll be the first to embrace change and leverage it for your own benefit — and you’ll also amaze potential employers.

When we think about quick learners, we might remember those few people back in our school and university days who just seemed to breeze through class. Or we’ll remember that memory champion with the unique ability to somehow remember not just the first six digits of pi (3.14159 btw) but 65,536. Sixty-five thousand! What an impressive feat. These people surely are special. Or they must practice all day, every day.

Here’s the thing, though: you can learn this skill too. There’s no superpower, reserved for a few gifted people, or something that can only be achieved with pills and supplements. Good news, huh?

Being a fast learner simply comes down to knowing how your brain (and body!) work and how to tailor your study activities accordingly. Everyone can do it. It’s a skill. Here’s how.

Don’t bother with time management. Manage your energy. First things first: it doesn’t really matter how much time you spend learning.

There, I said it. Pulling an all-nighter before your exams, participating in a 12-hour-YouTube-study-with-me session, or starring at your books long after midnight, aren’t just unnecessary. They actively sabotage your progress.

Sure, you need to invest time to learn a new skill. But even more importantly, you need to invest energy.

Think of energy as the most relevant resource in your learning endeavor. Your brain’s ability to grasp new concepts or to come up with new ideas doesn’t so much hinge on the time you spend on taking notes, but on your state of mind and available energy while doing so.

And energy is a finite resource. It helps to imagine your energy levels as something similar to your bank account. You’ve got a certain amount in there (hopefully) and maybe also some allowance for withdrawals beyond that. But at some point, you’ll have to recharge things or you’ll run out of steam.

Let’s take a closer look.

If you’re one of the 20% of American students who routinely pull an all-nighter during semester time, you should know that science thinks very little of this strategy for improving your output. To the contrary, sleep deprivation is linked to poorer performance across the bench and will likely hinder your long-term memory formation.

So while all-nighters make for good stories, they won’t do much for you in terms of learning effectively (and sustainably).

What’s more, because we’re so used to measuring our study efforts by time, we start using these crazy long sessions as benchmarks for us to achieve again, leaving us disappointed and frustrated whenever we don’t reach them.

Instead of measuring the quantity of study time, we should prioritize the quality. Put in a few hours of high energy work in each day and you’ll vastly outperform your former night-shift-zombie-self.

I have some bad news for you: if you’re hoping to learn something passively in your sleep by playing a lecture in the background, it’s not going to work. This hack to boost your learning has failed the scientific test.

The good news, however, is that you really can learn in your sleep. It just works slightly differently. So-called slow wave or non-REM sleep cycles help your brain to turn short-term inputs into long-term memories. What’s more, this process helps your brain find patterns and connections with existing ideas, thus increasing your creative problem solving potentials.

But it doesn’t stop there. Sleep also helps you reset your brain’s capacity to take in new information. So the next time you’re feeling like your head is filled to the brim and you just can’t practice anymore, consider taking a break to nap or get a good night’s sleep.

So while you can’t use your sleep time to put more information into your brain, a night of good sleep is crucial to sort through what you’ve learned during the day and to make sure that you retain it long-term.

If you struggle with this, here are some ideas for getting more sleep:

- No caffeine after 2pm. While the effect of caffeine sets in nearly immediately after drinking, it remains for hours in your system. Six hours after consumption, half of the caffeine will still remain and affect your sleep.

- Establish a night and morning routine. A night-time routine signals to your body that it’s time to power down. And the proper morning routine sets you up for success and ensures you don’t spend your first hour after waking up doom-scrolling (and no, checking your social media in a specific order doesn’t count as a morning routine).

- Avoid highly stimulating activities before bed. Help your body (and brain) to get into night mode and don’t pump up the energy levels close to bed time. Things to avoid include intense workouts, energizing music, heavy food, exhilarating readings or all-too-tense TV shows.

- Improve your sleeping environment. While many factors contribute to a good night’s sleep and not everyone can splurge on the latest mattress trend, there are lots of things you can easily implement to get a good sleep. Most importantly, have a dark room with no or minimal light sources. If needed, invest in some light-blocking curtains (there are lots of very affordable options). And ideally, leave your phone outside the bedroom.

Once you’ve got your energy levels up and stabilized, and you’ve had a good night’s sleep, it’s time to turn your focus to … your focus.

“Focus” in this context means your ability to actually sit down and study a topic. It’s the skill that stops you from cleaning up your room for the third time this week instead of tackling that new chapter in the book.

No matter how much energy you’ve got, if you can’t channel it into your learning project, if won’t be of much use.

A tomato will actually will help your learning skills. The so called Pomodoro Technique (pomodoro is the Italian word for tomato) is named after the tomato-shaped kitchen timer used by its inventor.

Using a timer also happens to be a very effective approach for supercharging your study sessions.

Here’s how it works:

- Set your timer for 25 minutes. (It doesn’t have to be shaped like a tomato, but it would be kinda cool.)

- Study. Don’t interrupt your learning session for anything. It’s just 25 minutes. Pretty much anything can wait until you’re done.

- Once the timer rings, stop immediately. This trains your brain to expect clear borders between study time and break time and makes it more likely to actually focus during the 25 minutes.

- Take a quick break of five minutes. Avoid overly stimulating activities (so ideally, don’t start scrolling social media). Instead, stretch a bit, watch your breathing or de-clutter the sixteen coffee mugs that have somehow accumulated on your desk.

- Repeat two or three more times before taking a longer break.

Why does it work?

Multitasking is a myth. Your brain isn’t wired to do two things at a time. Instead, it quickly switches between tasks. And each switch costs mental bandwidth. Context switching takes a much bigger toll than we assume. Quickly answering a text during your study session doesn’t just cost two minutes. Research shows that it can take up to 25 minutes to get back into a focused state.

But when we decide to study for the next two hours, it’s hard to fight back distractions constantly. Instead, it’s easy to pick up the phone to “just quickly check my messages” or respond to that one semi-urgent email you know is sitting in your inbox.

So instead of hoping that you’ll somehow manage to stay focused for two hours despite countless possible interruptions, create smaller, more intense study sessions and learn to clearly distinguish between study and break time.

There are many potential reasons for procrastination. A task might be perceived as too difficult or too unstructured. Or it might simply bore you. But whatever it is, our internal resistance is usually strongest before we start a task.

Here’s where the five-minute rule comes in. It’s a simple trick to convince yourself and it will work, even if you know that you’re about to trick yourself.

The next time you feel procrastination creeping in, make a deal with yourself to get started on the task for five minutes only. After those few minutes, you’re allowed to stop and do something else. Chances are, though, that you’ll continue with the task at hand because you’ve already moved past the first hurdle and gained some momentum.

It also pairs neatly with the Pomodoro Technique. Whereas the Pomodoro Technique is geared towards reducing distractions during your work sessions, the five-minute rule is the ignition for each individual session.

Anyone who has read Atomic Habits, by James Clear, has realized how big an impact your environment has on your subconscious behavior. This is as true for your learning process as it is for habit building. You’ll want to design your environment to support your study efforts instead of working against them. Here are a few guiding thoughts:

- Put your phone in a different room and make it hard to access YouTube or social media. Recent studies have suggested that the perceived effort required for a task might be related to the estimated opportunity costs. Unfortunately, social media, video games or simply YouTube videos are all designed to be very, very attractive to our brain — so the perceived opportunity cost is high. Help your brain out and eliminate these alternatives to bring down the effort of another study session.

- Set up a simple routine at the beginning of each study session. It could be as simple as pouring a cup of tea and putting on some study music. What’s more important than the routine is that you signal your brain: now it’s time to learn. Maybe even plan out your whole study week.

- Along the same lines is the advice to separate your learning space from your relaxing space. Dedicated rooms are the best, but where this luxury isn’t an option, reserve a location only for learning. If everything in your room has to serve several purposes, it’s a good practice to remove all learning material after you’re done for the day and put it back only when the next Pomodoro session is due.

- Lastly, tidying up a room and decluttering your desk is a great way to reduce the information overload associated with unordered spaces. The same is true for your digital space. And no, having all files dumped on your desktop and relying on Apple’s Finder to discover documents is not a good approach to personal knowledge management.

With our newly acquired laser focus and the energy levels still sufficiently high, let’s take a closer look at what science has to say about acquiring new skills.

When we’re in school, we pick up a simple approach to learning. We listen to a teacher, write down notes, maybe read a book … and then write more notes. Once exam time comes around, we start to re-read our notes until we feel confident enough about the topic.

That approach is deeply flawed and not really tailored to the way our brain processes information and learns a new skill.

First, we don’t practice the new skills we actually aim to master. Chances are, you won’t be tested on “writing notes and re-reading them later”. You’ll have to pass a multiple-choice test or write an essay in school. Later, you might want to create a website, learn a new language or master a new song on the guitar. In each case, the the most effective way to learn something is to practice the actual new skill you’re trying to master.

This so-called active practice is important because our brain has a really hard time transferring knowledge and skill from one area to another. So if you want to make things easier for your brain, do the real thing and design your practice around your desired outcome — rather than the default path you’ve been taught in school.

Secondly, and probably even more importantly, re-reading notes is a bad idea for another reason. Our brains actually don’t acquire knowledge when we try to get an idea into our head. We learn by trying to get something out of there.

Research shows that re-reading notes is a very low value study activity. In the study, students were separated into four groups, working through the exact same thing with the following rules:

- the first one was allowed to read the material once

- the second was allowed to read the material four times

- the third was asked to create a mind map after reading it once

- the fourth group tried to recall the content of the material after reading it once

The fourth group outperformed all groups by a vast margin. Trying to remember what you’ve read was more effective than re-reading the content another three times.

So the key to learn faster and improve your long-term retention is to constantly test yourself on new knowledge. Re-reading won’t help your brain cells nearly as much as actively trying to answer questions on the topic. This self testing strategy is known as active recall (or active practice), and it will be your new best friend when it comes to learning.

If you’ve ever tried to recall some of the more advanced lessons of your school or university career that you hadn’t revisited in a long time, you’ve probably experienced the Ebbinhaus Forgetting Curve.

Put simply, you’ll inevitably forget things over time. On the bright side, with a bit of strategic repetition, you can greatly improve long-term retention.

The key is to space out individual study sessions instead of clumping all the time practicing together. Studying three times a week for an hour, four weeks in a row is more effective than studying the same amount of hours in a single day. This is called distributed practice, also known as spaced repetition.

If you want to implement spaced repetition in your learning sessions, you have a bunch of options, depending on the level of complexity and customizability you desire:

- Anki is the most popular open-source tool for creating flashcards with built-in, spaced repetition. It’s a great tool for beginners.

- RemNote is a more advanced hybrid between a note-taking and spaced-repetition tool. It has a higher learning curve, but offers huge potential.

- Notion is an all-in-one workspace app that offers the biggest flexibility, though it can be daunting to build a system from scratch with this tool. Using a pre-built template can be a good option.

When buying Lego, you can get a building kit with specific instructions and big, special pieces, or you can simply get a big bucket of small, colored blocks. The latter option means you’ll spend a lot more time building something out of this mass of uniform blocks.

Your brain works in a similar way. It’s not too amazing at handling several things at once. If I asked you to remember the letters A A B D G N P S U until the end of this article, you’d probably have a hard time focusing on the text. It’s only a few letters, but it’s about to create an information overload in your head.

The same thing would look vastly different if I instead told you to remember the acronyms NBA, USA and GDP (which happen to have the exact same letters).

That’s because your brain can use something called chunking to combine unorganized bits into bigger units, thus helping you to retain the information much more easily. It’s why learning basic math operations in your first year of school felt daunting, but they happen more or less automatically once you move on to more complex topics. Your brain has created knowledge chunks around those operations and has more resources available to tackle advanced problems.

Leverage this to your own advantage by looking for ways to chunk new bits of information together. This is particularly important when you’re faced with a new concept, as you’re less likely to have existing knowledge structures in place.

So the next time you’re learning key points in a new area, or just getting started with some new material, don’t just create arbitrary lists. Instead, aim to organize information by meaning, connections and any sort of non-formal criteria.

To round things out, here’s a closer look at two very useful and effective learning strategies.

Few things will improve your learning as much as getting into the habit of explaining your newly acquired knowledge to others.

Coined after the famous physicist Richard Feynman, the Feynman Technique is all about breaking an idea or concept down into its components and explaining it (in your own words) as simply as possible.

To get into the right mindset, it helps to imagine that you’re explaining the new concept to a child.

First, take an empty sheet of paper and write down everything you know about the concept. Lay out the main points in a way that makes sense to you. Don’t use any primary sources to do so. Rely only on your current level of understanding.

Only when you get stuck somewhere, go back to the original source to fill in the blanks. That way, you make sure that you actually know what you don’t know — a step that’s often more difficult than looking for the right answer.

Once done, go through the explanation again and check for friction. Is there a coherent structure? Where are you relying on an assumption you don’t fully understand? Where do you hide behind complexity without really getting the gist of it?

Lastly, simplify your explanation as far as possible. Where are you using technical terms that would stop an outsider (or child) from understanding? Is there a metaphor or example that you could introduce to make things easier?

As you can see, this isn’t a strategy for any sort of new information. It’s a lengthy process that should be reserved for the key points of a new topic. But apply it to complex questions and see how new concepts quickly become a lot more intuitive.

The specific skills required to create a great website are plentiful. You need to understand layout and design; understand user needs and how they’ll navigate your site; and of course you’ll likely need to know how to write some code. You need to be able to combine a lot of different skills in order to deliver the desired result.

The problem with such complex topics is the lack of clear feedback when performing the task.

Feedback is crucial to any learning endeavor. It’s simple in theory: you compare your actual results with the desired results. But good feedback is hard to come by. Often, it’s your end results that are graded or evaluated. How does the website actually perform? Is it accomplishing your client’s goals?

But this means you always judge the sum of various factors and can’t really pinpoint easily where your biggest weaknesses are — and thus where your biggest potential for growth is. Higher-level feedback necessarily disregards some details. It’s noisy because it mixes together several skill subsets.

This issue can be tackled with drills.

A drill is about breaking a big task into smaller, separate components and practicing them in isolation. Create a lot of different website designs and judge them simply for their aesthetics. Hone in on the user journey and disregard all other factors. Try to write the sleekest and most elegant code possible for a random, given design.

Not only does this increase the relevance of the feedback, but it will also help you train your skills without the serious time commitment required for the complete task. You’ll also improve your skills faster, because you can identify your greatest weaknesses, thus increasing the marginal utility of your learning sessions.

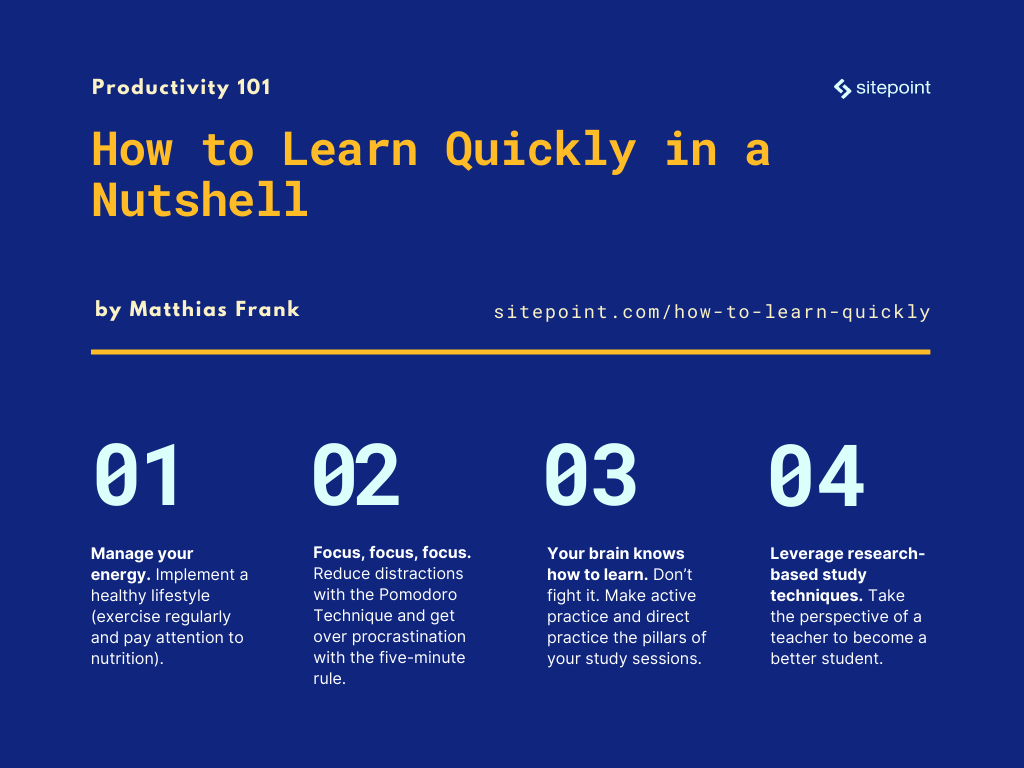

To wrap up, let’s revisit the lessons we’ve shared in this article:

- Manage your energy. Implement a healthy lifestyle (exercise regularly and pay attention to nutrition). And never, ever, trade in a good night’s sleep for a bit more cramming.

- Focus, Focus, Focus. Reduce distractions with the Pomodoro Technique and get over procrastination with the five-minute rule. Also set yourself up for success by designing your environment to help you and not hinder you.

- Your brain knows how to learn. Don’t fight it. Make active practice and direct practice the pillars of your study sessions. Use space repetition and chunking to make long-term retention easy, like playing with Lego pieces.

- Leverage research-based study techniques. Take the perspective of a teacher to become a better student. And eliminate your weak areas by drilling deep during your practice.

If you’re interested in learning more, check out this collection of articles on effective learning. And if you’re ready to start your own learning journey to become a developer, don’t miss out on our Ultralearning System specifically designed with these principles in mind.